Proud to Protect Burkinabè from Meningitis

In a remote village of Burkina Faso, a woman around 60 years old lined up to get vaccinated with the meningococcal serogroup A conjugate vaccine (MenAfriVac®, MACV) during a recent vaccine campaign. The health workers explained that she could not get the vaccine because of her age. She said she would not go back home without receiving “le bon vaccin” because she wants to live longer in order to take care of her grandsons, whose mother passed away.

This story illustrates that demand for MACV is very high in Burkina Faso. For the people of Burkina Faso, meningitis is a very dangerous disease and everybody is afraid of it. So, MACV is seen as a fabulous medication to prevent serogroup A meningococcal disease. People of all ages seek to be vaccinated and we don’t have problems trying to encourage people to get the vaccine. Burkina Faso was the most affected country in sub-Saharan Africa in terms of meningitis disease and death, and experienced numerous severe meningitis epidemics in the past four decades. Sadly, meningitis has touched almost every family in Burkina Faso.

Dr. Isaïe Medah, Director General of Public Health, Burkina Faso Isaïe Medah, MD, MSc, is a physician and director general of public health in Burkina Faso. Previously he was director of the country’s routine immunization program from 2015–2017 and director of disease control from 2011–2015.

Public Health in Practice

As a public health scholar, a former director for disease control, and the current director general of public health, my role is to design and coordinate the implementation of a preparedness and response plan to prevent outbreaks. I am also responsible for effectively managing the response when an outbreak does occur. This includes implementing a meningitis vaccination program, establishing a strong surveillance system, and building capacity and social mobilization. My role is also to coordinate partners’ interventions within Burkina Faso.

Initially, Burkina Faso held a successful mass vaccination campaign in 2010 targeted to people under 30 years old. Children born since the 2010 campaign were not protected, so in 2016 we decided to add MACV to our routine childhood vaccination program, and conduct a second catch-up vaccination campaign targeting children younger than 5 years old.

During this campaign, I spent time in the field meeting with the community. I recall one encounter with a 70-year-old man who told me that it is better to vaccinate old people first so that they can take care of their sick children. For him, vaccinating children was not a good strategy because children cannot take care of their ill parents. If the parents die, it leaves the children suffering. For him, “le bon vaccin” can help old people live longer and healthier lives. I understood this man’s concerns, and spent time explaining to him and others throughout the rest of the campaign why we were concentrating efforts on children. I believe that Burkina Faso has success with our vaccination campaigns because we always include communication in our planning. During visits in the field, we sensitize the community to the vaccination strategy and why certain ages are targeted. To the 70-year old man, I explained that these targeted public health measures can also help to prevent meningitis in the general population.

Reaching the People of Burkina Faso

A child lines up to get her routine MACV vaccination in Burkina Faso in 2017. © Evelyn Hockstein/CDC Foundation

When we do need to get the message out about vaccination, we use various communication and administrative channels and social networks to interact with the Burkina Faso population. Local radio and TV stations, as well as community speakers, communicate about meningitis. Political leaders, religious leaders, and stars of all kinds contribute to sensitize people about meningitis. Social events (e.g., markets, funerals, weddings) are used to give information to people.

The media has reported rumors at times, which created panic within the community. As people are more likely to believe what they see in the news and on social media, as public health officials, we must react quickly to share the correct information and the actions we are taking to respond to public health emergencies.

Partners Work Together in Burkina Faso

Protecting people from meningitis has been stressful, but also exciting and rewarding. Personally, I work well under pressure. The fight against meningitis was one of the most thrilling positions I held within the Ministry of Health, because I was eager to succeed and make a difference.

It was collaborative, inclusive, multisectoral, and interdisciplinary work. I collaborated with partners such as CDC Atlanta, the World Health Organization (WHO), Agence de Médicine Préventive (AMP), and many other non-governmental organizations operating in the health sector. We shared experiences and learned from each other. Managing meetings with stakeholders was exciting during outbreaks, trying to mobilize partners to achieve targeted objectives.

I was fortunate to establish long, continuous, and fruitful collaborations, particularly with CDC Atlanta (the Meningitis and Vaccine Preventable Diseases Branch), WHO, and AMP. CDC Atlanta assisted the Ministry of Health to set up robust meningitis surveillance, the best within countries in the African meningitis belt. As part of MenAfriNet, several West Africa countries adopted the so-called “Burkina Faso model” of case-based meningitis surveillance. CDC Atlanta has strengthened lab capacities, and helped train hundreds of health workers on meningitis detection and response to meningitis outbreaks. I am most proud of Burkina Faso’s collaboration with CDC on evaluations of meningococcal serogroup A conjugate vaccine and other vaccines against bacterial meningitis. These collaborations have helped our country collect information to guide our vaccine programs and rid our country of serogroup A meningitis epidemics.

From Mass Campaigns to Routine Immunization

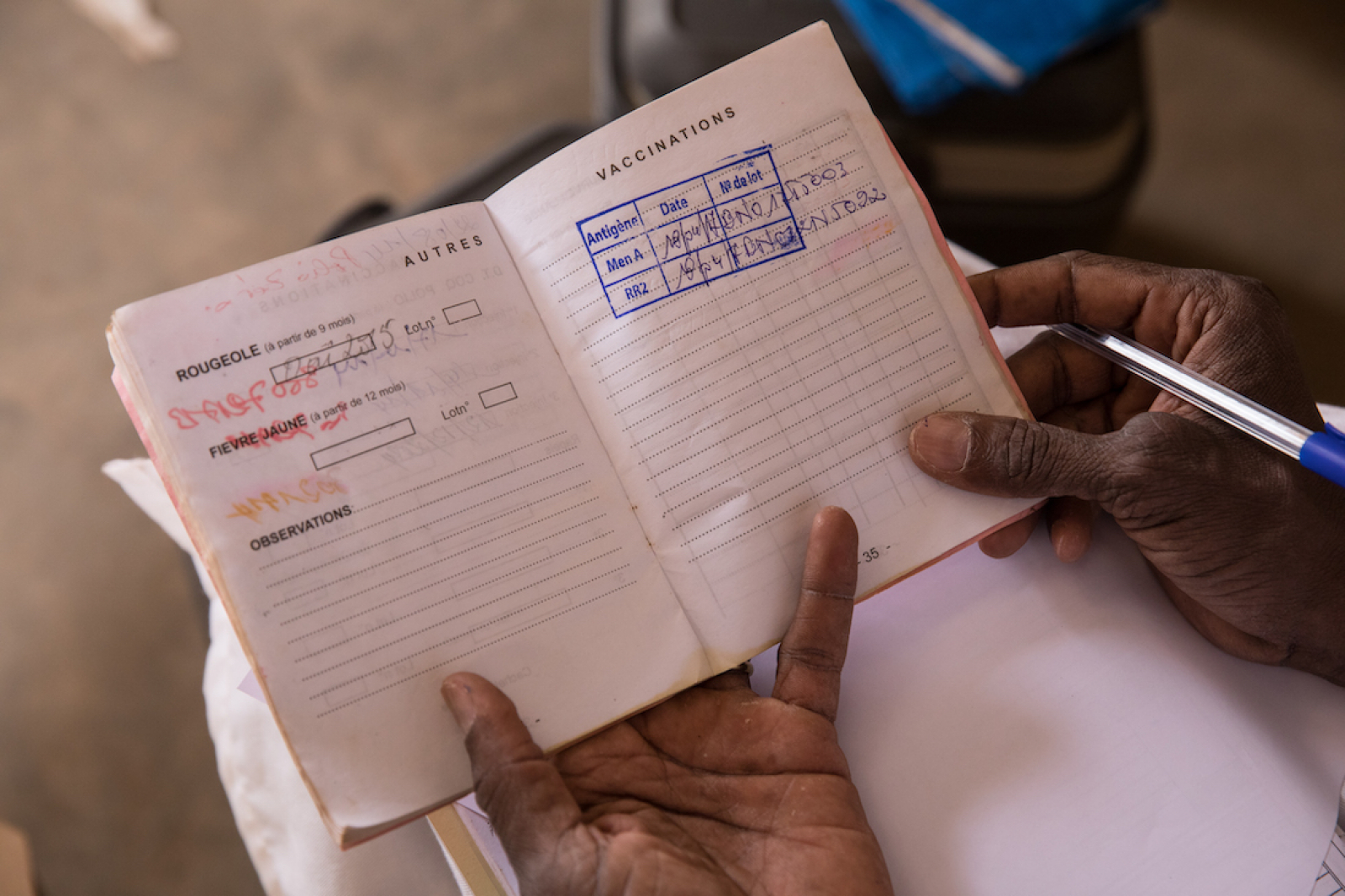

A childhood immunization record from Burkina Faso, 2017. © Evelyn Hockstein/CDC Foundation

During the first MACV mass campaign, I was very happy to see people striving to get vaccinated. When done, the campaign covered 100% of the targeted age group. Since the campaign, we have reported only four cases of serogroup A meningococcal disease. Fortunately, last year I was in a position to coordinate MACV introduction into the routine immunization program, which began in March 2017. Burkina Faso became one of the first countries to add this vaccine as a routine childhood vaccination. The launch of the introduction was led by the Minister of Health himself and it was very successful. Since 2010, Burkina Faso has been free of meningitis epidemics due to serogroup A—I’m proud of that accomplishment. It makes me feel so happy when I’m in the field and see children getting routinely vaccinated against a disease that has affected so many Burkinabè in my lifetime.

Since MACV is well accepted by the population in Burkina Faso, the Ministry of Health coupled a second dose of measles/rubella vaccine (MR2) administration with MACV. The goal is to boost MR2 uptake for children 15 through 18 months old, which is usually low. With the support of MenAfriNet (CDC Atlanta), we are currently conducting a survey on the impact of the introduction of MACV on MR2 coverage. We hope to have preliminary results of this study in mid-2018.

Moving Forward

The implementation of MACV has been a great success for Burkina Faso that should be built on. Our country still experiences significant meningitis disease and epidemics due to other pathogens. I believe we should continue developing new effective meningitis vaccines to defeat the remaining causes of epidemic meningitis. It is my hope that someday we will achieve the dream of a meningitis-free Africa.